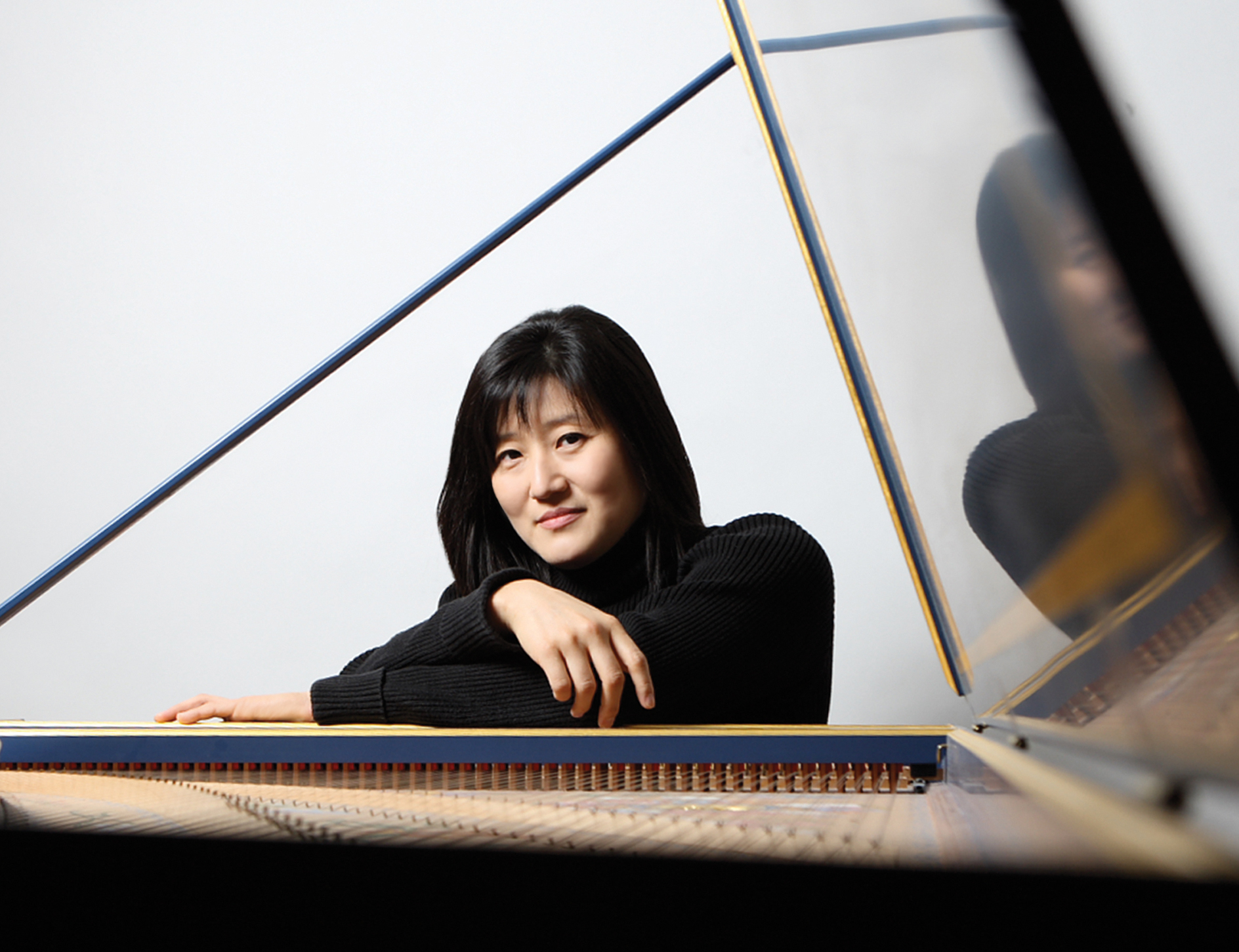

Junghae Kim

English

Korean American

United States

Summer 1991, Weekly Lessons 1993-1994

Individual private lessons

In public masterclasses as a player (participant)

In summer courses as a player

1991: Lessons and masterclass participation at Oberlin’s Baroque Performance Institute. 1993-1994: Weekly private lessons while also student at Sweelinck Conservatorium

My first contact with him was at Oberlin’s Baroque Performance Institute in the Summer of 1991. I wrote to him in 1992 and when he wrote back he remembered exactly what I had played for him in lessons and masterclass! He accepted me to study with him at the Sweelinck Conservatorium beginning in 1993 after he heard me at BPI. However he decided to retire from teaching at Sweelinck before my year, so he offered me the opportunity to study with him privately and of course I gratefully accepted this opportunity. As it turned out, it seems that I was one of his last official students.

Bachelor of Music, Peabody Conservatory 1988, and Master’s in Historical Performance (Harpsichord), Oberlin Conservatory of Music 1993. I had begun playing the piano at age 5 in Seoul, South Korea and when I was a sophomore in high school I won a nationwide competition sponsored by the American Embassy where the prize included coming to the United States to study. I later entered the Peabody Conservatory where I first met the harpsichord and fell in love with the instrument. I studied with Webb Wiggins there and Mr. Leonhardt’s recordings opened my eyes to the beauty and possibilities of baroque music during my undergraduate years. I would likely not have pursued early music with such a passion had it not been for what I heard in those recordings. After completing undergraduate studies, I studied with Lisa Crawford privately in Oberlin, OH, before enrolling as one of her first students in Oberlin’s then brand new Master’s program in Historical Performance. After I completed my Master’s with her at Oberlin, I was accepted to study with Mr. Leonhardt and won a Haskell scholarship that supported my studies with him privately, as well as my concurrent study with Bob van Asperen at the Sweelinck Conservatorium that led to an Advanced Certificate in Harpsichord Performance.

We worked on a lot of 16th & 17th-century and high baroque composers: Byrd, Bull, Farnaby, Tomkins, Frescobaldi, Rossi, a lot of Sweelinck, Froberger, Buxtehude, J.S. Bach and his family: especially the Well-Tempered Clavier, solo concertos and partitas and other suites, Louis Couperin, d’Anglebert, Rameau, Duphly, Royer, Scarlatti, Soler, Forqueray, Le Roux and others.

Only once, never twice! No, it was his choice, this is how he worked.

I had weekly lessons with him for over a year; sometimes he was out of town for concerts or conducting and we would have longer lessons or multiple lessons in a week to make up for the missed ones. Lessons were always at his home on the Herengracht and lasted at least 2 hours each. My very 1st lesson with him was quite memorable in many ways. I played my entire Master’s recital for him in one lesson and after completing the last piece at nearly the three hour mark, he said “ it is very good, do you have more music to play for me?” I was shocked. After that lesson I survived by preparing my weekly repertoire composed of half new pieces and half pieces I already had in my fingers (but had not played for him) in order to keep up. The instrument that I used was a Mietke, from Bruce Kennedy. It was a lot lighter than the instrument that I was renting at that time. It had a beautiful sound and touch with tortoise shell decoration. I still remember thinking, “When I own my own instrument, I am going to keep it in top shape like his,” and since buying my instrument I have always done so. I broke a quill during one lesson, and he pulled out his bag and he fixed it right away. It was great fun watching him and talking about his antique collection as he did so. We often conversed about non-musical topics and it was always fun. Once or twice I had lessons back to back for 3 straight days. We called these block lessons. It happened after Mr. Leonhardt was on tour performing and/or out of town; this is how he made up missed lessons. For me, I entered survival mode on these occasions. If you can imagine giving three different 90-minute solo recitals over three days you will have the right picture. After the 1st day out of a 3-day marathon, looking forward to the 2nd and 3rd days, I thought I would die. But I managed and was so grateful to be able to learn so much from him. Mr. Leonhardt would play a few times during lessons; to demonstrate articulation, phrasing and to provide examples of the variety of sounds and touch possible on the instrument. He would usually ask, “May I?” Which meant I was to get up and cede him the chair so he could play the entire piece or section.

There was never any discussion about keyboard technique, fingerings (early or modern fingerings), hand / arm position, etc. My impression was that he expected any of those issues to have been dealt with prior to coming to study with him. Once during one of our breaks to have tea, he mentioned to me that he didn’t have much belief in teaching. He thought one either had what it takes to be a musician or one does not. He once said he felt very lucky that he did not have to teach any “hooligans”; at which point I guessed that I was, at least, not considered a hooligan in his eyes. Mr. Leonhardt often spoke about dynamics in musical phrasings and was able to demonstrate them himself if I was not hearing it or getting it right away. It was far easier learning this way; hearing and watching him perform was worth innumerable words and I appreciated his approach. Once I asked him how he could make one note sound louder than a g minor chord (in a d’Anglebert g minor suite Sarabande ). I heard him do it, and told him so. He just smiled and said, when you are playing it you may be thinking of it as louder, but you must think harder. Over time, I came to understand how to do this; mostly from listening to how he accomplished it.

I think he assumed that I had already accessed that information before becoming a student of his. Before performing a piece for him I would always have to present the source of the piece, when it was published, and so on, just a short description. He would mention ornament tables in passing, assuming that I already knew them.

He was excited about Frescobaldi and went into a lot of detail about the characteristics of his composition and the temperaments used, articulation etc. He played some pieces by Frescobaldi during one of my lessons; pieces that I was not playing for him at the time, to give me a sense of the style. This was unusual because he would normally either not play at all, or if he were to play it would be what I was playing. He was enthusiastic about 16th and 17th-century music, especially Byrd, Froberger, Sweelinck, Louis Couperin, and d’Anglebert, and would relish talking about them. He would encourage me to see what is behind the notes in d’Anglebert and how important it was that the phrasings, articulation and dynamics help the musical line fall naturally.

He would suggest that there are other ways to play certain pieces (for example the Gigue from Bach’s Partita No. 6 may be played in duple or triple meter) and would ask me to consider articulating in a different way or phrasing in a different way and perform for him on the spot. He would ask why I chose a certain way and was interested in helping me see how different interpretations could be achieved with a piece. He never pushed a specific interpretation, but wanted me to be able to see pieces from many different angles and make my own decisions; not because I could only see one way to play it, but because I was able to choose from a number of different ways.

In my opinion (then and now) he was the greatest interpreter of baroque harpsichord music in the modern era and I wanted to learn as much as I could from him about how he thought about music, how he saw various composers’ styles, and how he achieved what he did on the instrument. I was also interested in hearing about what made him dedicate himself to this field of early music in the 1960s and what drove him. I wanted to see his point of view on how to approach a career in music. I wanted to learn enough to carry on his teachings into the future.

We exchanged a few letters over the years after I left. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the opportunity to visit him again in person, and the one time he traveled to the United States to perform after I completed my studies with him he visited only New York and did not come to the West Coast. However on one occasion, a few years before he passed, I heard from a good friend who had attended one of his concerts in Italy, that when he mentioned me to Mr. Leonhardt, he sent his regards. That was the last contact I had with him. I still deeply regret that I didn’t visit him before he passed.

Absolutely. My interpretations, my practice habits, and how I approach interpreting and performing pieces are all deeply influenced by his teachings and so I pass this on to my students. I research the background of pieces before I approach them, study how they are constructed, evaluate the many angles from which to approach different sections, alternative articulations, and so on. This is an approach that developed out of my work with him and I pass this on to my students. His approach was to see the performance of this music as a responsibility on the part of the performer to see past the notes to the meaning of what the composer intended, and to shape the music in a way that brings out the 'affekt' of the piece to the audience. He always encouraged me to “be true to the music” and would talk about the performance of music as not being about ego or anything petty like that. He saw being nervous or distracted as essentially selfish acts, and that maintaining a focus on taking something that is behind the notes and bringing it forward as being paramount. He encouraged seeing practice hours as being the most precious and intimate time between the music and the performer. His philosophical approach, always encouraging and polite, is something that I have taken with me as I teach my students.

At the time it was daunting to get through so much music at each lesson. It was exhausting, but at the same time it taught me how to practice correctly with mindful intent in order to be able to learn the amount of music that his lessons demanded. I had never worked with a teacher who would only listen to a piece once and then would want to move on. The amount of information I learned from him on each piece was astonishing; he had so much information to impart; both verbally and non-verbally through his example, that it was overwhelming at times. Looking back on it now, I appreciate how lucky I was to have had this experience, though it was difficult at times. When I was immersed in the experience I probably did not appreciate sufficiently the ability to immerse myself in music and study, to live every day thinking about what I was learning and preparing for the next lesson. Now as I practice, perform and teach I can still hear what he would say about the music on which I or one of my students is working.

Be true to the music and the rest will take care of itself. Talking less and playing more is the best way to communicate music. Relish the intimate time you have with the music during practice. Share what is behind the notes with others in a natural way. Performing is not about you; it is about bringing to life the message of the composer. His influence on my style of playing is woven too deeply into my playing and approach to summarize. While he never admitted to believing in the usefulness of teaching, his influence on so many aspects of my playing has proven him too modest. He was one of the kindest and most thoughtful people I have known. He once stood outside his home in the rain waiting for me with an umbrella to help me through the construction on the front of his home after my taxi was late in picking me up. His example then and so many other times proved that even the greatest of us can afford to be modest, kind and humble.

These were the most wonderful experiences of my life. Each week I would ask the taxi driver to take me to the Modern Art Museum because this would insure that they would find his place, which was next-door to his house on the Herengracht. The house itself was gorgeous and located in one of the finest neighborhoods. The house had traditional high ceilings, marble floors, and tall windows and the harpsichord was placed next to the window. Mr. Leonhardt was always gracious and kind and greeted me at the door or outside his home to assist me in navigating the entrance that, at that time, was complicated by scaffolding. He would assist me up the stairs at the front because I use crutches. Occasionally, Mrs. Leonhardt brought in cookies and tea on a beautiful tray full of delft dishes. As she was handing the tray to Mr. Leonhardt, I would ask her to join us, but she always deferred. Mr. Leonhardt would always refer to me as Ms. Kim, though I had asked him to please call me JungHae on a number of occasions…but he never did. He always preferred the formal honorific. Each lesson took place in the sacred space he created, enhanced by the setting in a historic home. The intensity was incredible, but this made the rewards that much more special. His passing has left a deep and abiding sense of sadness in my heart, but the gratitude and respect I have for Mr. Leonhardt, for his teachings, his wisdom, and his humanity fill me with a sense of purpose to carry on his legacy as best I can.

Korean-born harpsichordist JungHae Kim earned her Bachelors degree in Harpsichord Performance at the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, MD, where she studied with Webb Wiggins. She then earned a Masters in Historical Performance in Harpsichord at the Oberlin Conservatory with Lisa Crawford, before completing her studies with Gustav Leonhardt in Amsterdam on a Haskell Scholarship. While in the Netherlands she also completed an Advanced Degree in Harpsichord Performance under Bob van Asperen at the Sweelinck Conservatorium. Ms. Kim has performed in concert throughout United States, Europe and in Asia as a soloist and with numerous historical instrument ensembles including the Pierce Baroque Dance Company, the Los Angeles Baroque Orchestra, Music's ReCreation, The Two, Musica Glorifica and the Seoul Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra. She performed at the Library of Congress with American Baroque and frequently performs with her Bay Area period instrument group; Ensemble Mirable. As a soloist and chamber musician she has performed with Musica Angelica, Brandywine Baroque, the New Century Chamber Orchestra, the Zurich Chamber Orchestra, and the San Francisco Symphony. In 2016, she produced and performed a remarkable concert in Berkeley, CA with guest artist Sigiswald Kuijken. Ms. Kim has been featured in an episode of Classical Odyssey (Korean Broadcast System; South Korea) and has been interviewed on Public Radio (Cleveland Public Radio, Hawaii Public Radio, Los Angeles Public Radio). She is a sought-after instructor; having presented masterclasses and lectures at institutions across the globe including the San Francisco Conservatory, Dongdok University (Seoul, South Korea), and Kwangju National University (Kwangju, South Korea), Pomona College, and the University of Nebraska. Ms. Kim has also been invited to judge a number of musical competitions in the U.S. Her students have gone on to graduate studies in harpsichord at Boston University, Julliard, SUNY-Stony Brook, and the University of Michigan. JungHae has frequently taught and performed at summer music festivals including the Hawaii Performing Arts Festival, the Music in The Vineyards Festival (Napa), the Britt Festival (Oregon), the Bloomington Early Music Festival (Indiana), the Berkeley Early Music Festival, the ChunCheon International Early Music Festival (South Korea), the Twin Cities Early Music Festival (Minnesota), the MidsommerBarok Festival (Copenhagen), and as a chamber musician and soloist at the Assisi Music Festival in Italy. She has also worked to further early keyboard performance in the San Francisco Bay Area through her work as Co-Director of MusicSources, Center for Historically Informed Performance. JungHae’s performances have been described as inspired, fluid, engaging, emotionally exquisite, warm, and inviting. Her unique style blends a sparkling virtuoso technique with a gentle and lyrical sensibility that makes music of this genre instantly accessible to the modern ear. With Ensemble Mirable, Ms. Kim has released a number of fine chamber music recordings including the world premier of Six Cello Sonatas by Jean Zewalt Triemer (awarded honorable mention in the 2nd annual EMA/Dorian recording competition); Conversations Galantes, the Music of Louis Gabriel Guillemain; and Influenza Italiana, Glorious Music of the Italian Baroque. She soloed on four of J.S. Bach’s 13 harpsichord concertos with Brandywine Baroque Orchestra on a recording entitled: Johann Sebastian Bach Complete Harpsichord Concertos on Antique Instruments, released on the Plectra label. She has released three recordings of solo harpsichord works including: The Virginalists; an exquisite collection of works by d’Anglebert entitled Jean Henri d’Anglebert Pièces de Claveçin (1689); and a two-volume set entitled J.S. Bach: Suites and Fantasias.

GL the art os fugue book image-5eeaecdf82dcd.pdf

Gustav Leonhardt Acceptance to private study letter-5f04bdfc02cc3.pdf

Gustav Leonhardt Correspondance Thank you and NY Concert-5f04bdfc03937.pdf

Gustav Leonhardt Thank you Letter-5f04bdfc04400.pdf

JungHae Kim Korean Translation for Leonhardt Pedagogy Project-5f2a56235328a.pdf

February 16 2012 Korea Times Article, Mr. Leonhardt-5f2a610188f2c.pdf